“Functional neurological disorder”, a practical approach

Some patients present with neurological symptoms that are inconsistent or incongruent with neurological disease

Different terminology is used:

a. Psychogenic, psychosomatic, and somatization (an exclusively psychological etiology)

b. Functional neurological disorder: a problem due to a change in function of the nervous system rather than structure (the preferred term)

c. Nonorganic

d. Medically unexplained

e. Hysteria

Definitions & Classification

Terminology of “Functional neurological disorder”:

Conversion disorder (intolerable psychological conflict leads to the conversion of distress into physical symptoms)

Somatization disorder is applied to a patient with a history of symptoms unexplained by disease, starting before the age of 30. The current definition requires at least 1 “conversion” symptom, 4 pain symptoms, 2 gastrointestinal symptoms (usually irritable bowel syndrome), and 1 sexual symptom (dyspareunia, dysmenorrhea, or hyperemesis gravidarum)

Hypochondriasis describes excessive and intrusive health anxiety about the possibility of serious disease

Factitious disorder describes symptoms that are consciously fabricated for the purpose of medical care or other nonfinancial gain

Malingering is not a psychiatric diagnosis but describes the deliberate fabrication of symptoms for material gain

Epidemiology of “Functional neurological disorder”

One-third of neurological outpatients present with symptoms the neurologist does not think relate to neurological disease

In half of these (around one-sixth of all patients) the neurologist makes a primary “functional” or “psychogenic” diagnosis

The rest have some neurological disease but symptoms out of proportion to that disease

Patients with functional neurological symptoms have much physical disability and are more distressed than patients with neurological disease

Key diagnostic features

The four key diagnostic features of “Functional neurological disorder”:

a. Neurological symptoms involving motor or sensory symptoms or loss of consciousness

b. No evidence of organic (neurological) disease that can explain the symptoms

c. Associated psychological stressors (relevant to onset of

d. symptoms)

e. Conscious simulation (feigning) is excluded

Do not always expect psychological comorbidity or life events

Misdiagnosis of “Functional neurological disorder”

Mistakes occur when:

1. Too much weight is placed on the presence of a psychiatric history

2. The diagnosis is made just because the problem is bizarre or unfamiliar

3. There is failure to consider the possibility of a comorbid neurological disease (e.G., Nonepileptic attacks and epilepsy in the same patient)

4. When the assessing clinician is unfamiliar with a wide range of unusual neurological disorders

5. La belle indifference (smiling indifference to disability) has no diagnostic value, since it may be present in neurological disease

Specific syndromes in “Functional neurological disorder”

Pseudocoma

1. Eyelid tone: The malingering or hysterical patient often gives active resistance to passive eye opening and may even hold the eyes tightly closed

2. Blinking: increases in psychiatric and malingering patients but decreases in patients in true stupor

3. The pupils normally constrict in sleep or coma but dilate with the eyes closed in the awake state. Passive eye opening in a sleeping person or a truly comatose patient (if pupillary reflexes are spared) results in pupillary dilation

4. Roving eye movements cannot be mimicked and thus also are a good sign of true coma

5. If during caloric testing, the eyes do not tonically deviate to the side of the caloric instillation, and the fast phases are preserved, stupor or true coma is essentially ruled out. Cold caloric testing with the resultant vertigo usually “awakens” psychiatric and malingering patients

Pseudoseizure

Psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES) are paroxysmal episodes of altered behavior that superficially resemble epileptic seizures but lack the expected EEG epileptic changes

the most common imitators of seizures and epilepsy

However, as many as 40% (10-15% in newer studies) of patients with nonepileptic seizures also experience true epileptic seizures

PNES are diagnosed in a considerable proportion of patients referred for drug-resistant seizures(1.4 and 4.6 per 100,000 person-years of observation)

Establishing the correct diagnosis often requires observation of the patient’s clinical episodes, but complex partial seizures of frontal lobe origin may be difficult to distinguish from nonepileptic seizures

more common in females (70-80%), more common between 15-45 yrs

Three broad categories: psychogenic motor seizures with prominent motor activity, psychogenic minor motor or trembling seizures with tremor of the extremities, and attacks with motionless unresponsiveness or collapse

Most frequently, they superficially resemble tonic-clonic seizures

They generally are abrupt in onset, occur in the presence of other people, and do not occur during sleep

Motor activity is uncoordinated

urinary incontinence and physical injury are uncommon

Nonepileptic seizures tend to be more prolonged than true tonic-clonic seizures

Ictal eye closing is common in nonepileptic seizures, whereas the eyes tend to be open in true epileptic seizures

During and immediately after the seizure, the patient may not respond to verbal or painful stimuli

Cyanosis does not occur, and focal neurological signs and pathological reflexes are absent.

In the patient with known epilepsy, consider the diagnosis of nonepileptic seizures when previously controlled seizures become medically refractory

In some patients with psychogenic seizures, the clinical episodes frequently precipitate by suggestion and by certain clinical tests such as hyperventilation, photic stimulation, intravenous saline infusion, tactile (vibration) stimulation, or pinching the nose to induce apnea. Hyperventilation and photic stimulation also may induce true epileptic seizures, but their clinical features usually are distinctive

Findings on the interictal EEG in patients with pseudoseizures are normal and remain normal during the clinical episode, demonstrating no evidence of a cerebral dysrhythmia.

With the introduction of long-term ambulatory EEG monitoring, correlating the episodic behavior of a patient with the EEG tracing is possible, and psychogenic seizures are distinguishable from true epileptic seizures

plasma prolactin concentrations may provide additional supportive data. Plasma prolactin concentrations frequently are elevated after tonic-clonic seizures, peaking in 15 to 20 minutes, and less frequently after complex partial seizures. Serum prolactin levels almost invariably are normal after psychogenic seizures, although such a finding does not exclude the diagnosis of true epileptic seizures

EEG-video monitoring is the most reliable procedure which remains the standard diagnostic method for distinguishing between epileptic and psychogenic seizures

Memory and Cognitive Symptoms

Cognitive symptoms are common among patients with functional neurological symptoms. They may be attributable to fatigue, anxiety, or low. Presentations include:

“Normal” absentmindedness and functional memory symptoms. In someone who is usually not absentminded, forgetting why they went upstairs, losing their keys, or losing track of conversation may be interpreted as abnormal. The patient reports variability in their memory problems and episodes when they forgot familiar information such as their own address and then remembered it again

Word-finding difficulty is a common symptom among patients with other functional neurological symptoms. They may also report mixing words up or neologisms, but true dysphasia is rare

Early loss of relatively “protected” knowledge such as the names of spouses or children, discrepancies between real-life function and test results

In such situations, cognitive “effort tests” may be useful. These are very simple tests that even patients with severe dementia or head injury should be able to perform well. For example, the coin-in-the-hand test involves 10 trials of showing a patient which hand a coin is held in, asking them to close their eyes for 10 seconds and then choose the hand with the coin

Psychogenic visual symptoms

Nonorganic (functional) visual disturbance can occupy up to 5% of an ophthalmologist’s practice

Nonorganic visual disturbances can have a variety of manifestations

Testing of visual fields is extremely important in patients with suspected nonorganic visual loss and may reveal one of several patterns including tubular constriction, cloverleaf constriction, spiraling isopters, crossing isopters, or inverted isopters

Lack of expansion of the visual field area with an increasing distance from the clinician suggests nonorganic visual field constriction

The use of visual-evoked potentials (VEPs) to diagnose nonorganic visual loss can be frustrating and unreliable

If the VEP is normal, useful information is gained, but factitious abnormalities in the VEP can be induced by normal persons who defocus their vision during the test. Therefore, an abnormal VEP is not always diagnostic of an organic visual disturbance

Double vision. Binocular diplopia is usually due to convergence spasm (asymmetrical overactivity of the normal convergence response)

This can be demonstrated by testing convergence movements but holding the finger at a close distance for longer than usual. When persistent, convergence spasm can resemble a sixth nerve palsy

Monocular diplopia is usually functional but can be due to ocular pathology

Triplopia is surprisingly usually related to an organic eye movement abnormality but can be functional

Speech and Swallowing Symptoms

Functional dysarthria usually takes the form of intermittent slurred speech or stuttering speech with difficulty starting words. Speech may be slow and with hesitations noticeably occurring in the middle of sentences

Dysphonia Functional dysphonia is a common presenting symptom to otolaryngologists but may be seen by neurologists in combination with other functional symptoms. Speech is usually whispering in nature and may follow an episode of laryngitis

Globus pharyngis, which describes the symptom of “something sticking” in the throat, even when the patient is not swallowing anything. There is controversy regarding how often this symptom can be explained by gastroesophageal reflux disease and appropriate levels of investigation

Functional weakness

Clues to functional weakness include the following:

1. Improvement in strength with coaching

2. Inconsistencies in examination—for example, inability to extend the foot but able to walk on toes

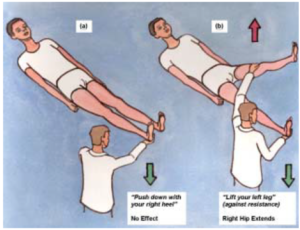

3. Hoover sign

4. Paralysis in the absence of other signs of motor system dysfunction, including tone and reflex changes

5. Pattern of weakness: In functional weakness, the limb is usually globally weak or often demonstrates the inverse of pyramidal weakness, with the flexors weaker in the arms and the extensors weaker in the legs

6. Hip abductor sign. demonstrating weakness of hip abduction which returns to normal with contralateral hip abduction against resistance

7. “Give-way” weakness. This is a pattern of weakness in which the patient transiently has normal power but then the limb gives way

Weakness as a functional symptom is more common in females and typically presents in the mid-thirties

Comorbidity with other functional symptoms, especially fatigue and pain, is almost invariable

The most common presentation is unilateral weakness with no good evidence for left-sided or nondominant preponderance, followed by monoparesis and paraparesis. Complete paralysis is less common

The onset is sudden in around 50% of patients. In the acute presentation, there are often symptoms of a panic attack, dissociative seizure, or an immediate trigger such as a physical injury, acute pain, migraine, a general anesthetic, or an episode of sleep paralysis

When the onset is more gradual, there is typically a history of fatigue, pain, or immobility on which the weakness becomes superimposed gradually over time

Figure 1: Hoover’s sign

Psychogenic movement disorders

In specialist clinics, these symptoms account for up to 10% of new referrals

The onset of functional movement disorders is often sudden or may be accompanied by pain

The course may be unusual, with sudden remissions or relapses in different limbs

Diagnostic clues:

a. Abrupt onset

b. Incongruous movements

c. Inconsistent movements

d. Response to placebo or suggestion

e. Selective disability

f. Dramatic resolution

g. Maximum early disability

h. Deliberate slowing

i. Rhythmic shaking

j. Bizarre gait

k. Improvement with distraction and worsening with attention

Psychogenic gait disorder

A gait disorder is one of the more common manifestations of a psychogenic or hysterical movement disorder

The typical gait patterns encountered include transient fluctuations in posture while walking; knee buckling without falls; excessive slowness and hesitancy; a crouched, stooped, or other abnormal posture of the trunk; complex postural adjustments with each step; exaggerated body sway or excessive body motion especially brought out by tandem walking; and trembling, weak legs

The more acrobatic hysterical disorders of gait indicate the extent to which the nervous system is functioning normally and is capable of high-level coordinated motor skills to perform various complex maneuvers

One must be cautious in accepting a diagnosis of hysteria, because a bizarre gait may be a presenting feature of primary torsion dystonia, and unusual truncal and leg postures may be encountered in truncal and leg tremors

characteristic types of functional gait disorder:

a. Dragging gait

b. Tightrope walker’s gait with arms outstretched as if walking a tightrope, often with lurches to one side or the other but good recovery of balance

c. Astasia-abasia, which refers to normal limb power and sensation on the bed but inability to stand and walk. This can occur in organic truncal ataxia and sensory ataxia

d. Crouching gait, which requires better strength and balance than a normal gait. Patients with this gait can be frightened of falling; this gait allows them to be closer to the ground

e. Knee-buckling gait, usually seen when the patient has unilateral functional weakness

Functional sensory loss

Functional sensory symptoms are common in patients with functional weakness and in patients with chronic limb pain

Misdiagnosis of functional sensory loss is particularly common with thalamic infarction and plexus dysfunction

Clinical presentations suggesting functional sensory Loss include:

a. Sensory loss exactly splitting the midline, with a minimal transition zone

b. Sensation cut off at the groin or shoulder

c. Circumferential sensory loss around the body or an extremity

d. Failure to perceive vibration with a precise demarcation

e. Alteration of vibration sense across the forehead or sternum

f. Loss of vision or hearing on the same side of the body as for the cutaneous sensory deficit

g. Total anesthesia

The discrepancies in total anesthesia can be failure to perceive any sensory stimulus on an extremity that moves perfectly well. This degree of sensory loss would be expected to produce sensory ataxia

If the anesthetic limb is an arm, examining for sensory abnormality while the arms are folded across the chest can be confusing for the malingering patient, especially if performed quickly

Touch the patient’s hand while his eyes are closed and ask the patient to “Say yes when you feel it and no when you don’t”

Investigations of “Functional neurological disorder”

Investigations will usually be necessary, partly because the presence of a functional symptom does not exclude a comorbid underlying neurological disease

It is worth considering how to perform them

Prescription of multiple tests and treatments may serve to reinforce the presumed presence of disease, thereby augmenting illness behavior

Try to do all the necessary tests at the same time and not sequentially, which tends to prolong the agony of “diagnostic limbo.”

Even if there are abnormalities on a scan, they cannot explain most of the patiemt’s symptoms and signs

Management of “Functional neurological disorder”

The acute symptoms can usually be mitigated by persuasion and demonstration. One tactic is to treat the patient as though she has had an illness and is now in the process of recovering

Sometimes a single symptom such as hemiparesis or tremor can be halted by a particular maneuver and this demonstration suffices to begin recovery

Performing placebo procedures is controversial

Detection and treatment of comorbid psychiatric problems such as anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, or obsessive compulsive disorder

Cognitive behavioral treatment

Psychodynamic psychotherapies

3 Comments

cosummitconstruction

27 April, 2019

It may be worth examining the strength of the sternocleidomastoid which is rarely weak in disease but may often be weak in unilateral functional weakness.

click this link here now dailymacho.com

11 October, 2020

Great news once again!

https://www.google.gg/url?q=https://dailymacho.com/

look at this web-site prankarmy.tv

11 October, 2020

I love reading your site.

http://images.google.co.ck/url?q=https://prankarmy.tv/