Myalgia, A Practical Approach

Myalgia, An Overview

Myalgia, or muscle pain, is a common complaint among adults presenting for medical care.

Nearly everyone will experience muscle soreness at some point in their life.

Unusually excessive exertion, trauma, and viral infections are among the most common causes. While many causes are benign and self-limited, myalgia may be the harbinger of disorders associated with significant morbidity.

In the clinical setting, patients describe muscle discomfort using a variety of terms: pain, soreness, aching, fatigue, cramps, or spasms.

Myalgia may be described as a poorly localized aching in a muscle or group of muscles, usually characterized as a deep aching sensation, but sometimes as a burning or electric sensation

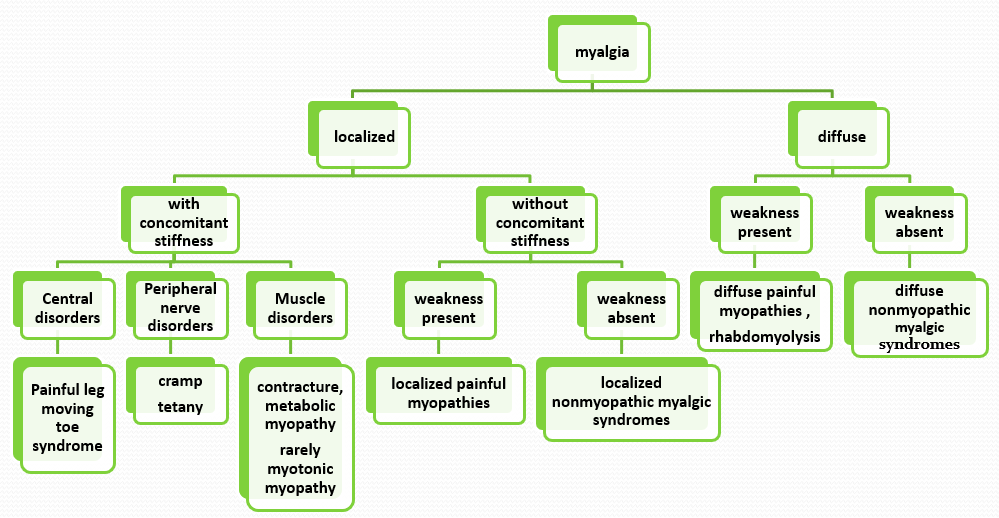

Classification of myalgia

Primary muscle disease vs. referral pain

- Acute (less than a month) vs. Chronic (More than 3 months)

- Localized (involving one or few muscle groups) vs. Generalized (Involving more than four areas)

- Episodic vs. Constant; in episodic form relation to muscle activity and concomitant muscle stiffness during the episode is important

- And with associated features: weakness, stiffness,…

Clinical classification of myalgia is summarized in figure 1.

Figure 1: Clinical classification of myalgia

Differential Diagnosis of Myalgia

See the complete list of differential diagnosis of myalgia in “NeuroAdvise” application. See the home page for more information: https://www.neuroadvise.com/

Approach to the Patient with Myalgia

A systematic approach including history, physical and neurological examination and selective use of laboratory and electrophysiologic studies are mainstay of management.

Early in the evaluation of patients with myalgia, the clinician should attempt to identify those patients with a serious or life-threatening condition.

Conditions causing myalgia may cause significant suffering, but true medical emergencies presenting with myalgia are rare.

Prompt diagnosis and treatment are required for bacterial infections, especially endocarditis and impending sepsis, which may present with diffuse myalgia, fever, chills, arthralgia, fatigue and back pain .

Rhabdomyolysis can present with diffuse myalgias, as well as renal failure and/or compartment syndrome in severe cases.

Investigation of patient with myalgia

For mild symptoms, watchful waiting without laboratory evaluation may be appropriate, as symptoms often resolve on their own with time.

However, for more significant symptoms (e.g., severe pain or muscle weakness), selected laboratory studies may be quite helpful in ruling in or ruling out conditions that remain in the differential diagnosis after a detailed history and physical examination.

As an initial assessment, complete blood count, urinalysis, measures of renal and liver function are appropriate for most patients with significant myalgia. Depending upon the specific symptoms and physical findings, measures of serum calcium, albumin, phosphate, TSH, CK, and 25-hydroxyvitamin D may be appropriate to assess.

The following tests may also prove helpful in certain clinical situations:

Laboratory Tests:

Blood cultures and serologic testing for infectious agent may be useful.

ESR, CRP — These may be helpful to identify the presence of systemic inflammation, as with infection and systemic rheumatic disease (especially polymyalgia rheumatica and inflammatory myopathy). On the other hand, a normal ESR is the expected finding in patients with fibromyalgia. However, caution must be taken in interpreting these test results as elevations in the ESR and CRP are not specific. In addition, normal or unimpressive results rarely rule out a particular cause of myalgia.

Autoantibodies, such as antinuclear antibodies (ANA) for suspected systemic lupus erythematosus, anti-neutrophilic cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) for suspected ANCA-associated vasculitis, as well as rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (Anti-CCP) antibodies for suspected rheumatoid arthritis, should be limited to those patients for whom there is at least a moderate pre-test probability of disease. Widespread testing with these autoantibody tests for all patients with myalgia is likely to produce an unacceptably high rate of false-positive results.

Testing of cortisol production, such as morning serum cortisol or adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) stimulation test, are helpful to diagnose or rule out adrenal insufficiency and as 24-hour urine cortisol testing to rule out Cushing’s disease; oral glucose load/growth hormone assay to rule out acromegaly

Imaging:

Radiographs, MRI, and other imaging tests are not routinely necessary in the evaluation of myalgia. Utility is limited to assessment of erosive arthritis (rheumatoid arthritis and others), fracture, inflammatory muscle disease, or localized muscle disease (pyomyositis, muscle infarction).

Neurophysiology studies:

Electromyogram (EMG) with nerve conduction studies (NCS) may be helpful to support the diagnosis of inflammatory or metabolic myopathy, as well as a neuropathic process.

Tissue sampling (eg, aspiration or biopsy):

Most patients with myalgia will not require tissue sampling. However, it may be diagnostic for patients with suspected abscess, inflammatory myopathy, vasculitis, or systemic lupus erythematosus.

4 Comments

AffiliateLabz

16 February, 2020

Great content! Super high-quality! Keep it up! 🙂

JamesDen

26 April, 2020

You have superb info right.

Janet

6 September, 2020

I got this website from my pal who shared with me concerning this

web site and now this time I am visiting this web page and reading very informative articles at this place.

Look into my webpage :: Calzoncillos Calvin Klein

Mason

17 October, 2020

Very good post. I will be facing some of these issues

as well..

my web page; nike free